|

|

| Vol 14|No 6|Summer|2005 | |

Power

by Jamie McKenzie

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I. The Comprehension---Literacy Link

While we have always known that a thriving library program is central to the success of a school's reading and learning programs, “The times, they are a-changing,” as Dylan would put it. What once was central is now urgent. NCLB1 has created a cocktail of pressures, risks and opportunities that impact dramatically on the roles of media specialists. The LMS (teacher-librarian) is now a critical factor in a school's survival, especially as the staff works to strengthen reading comprehension across all classrooms and disciplines. If the teacher-librarian becomes the most capable teacher of comprehension skills in the school, the prospects for a strong school and a thriving library program are enhanced dramatically, especially when the teacher-librarian has the ability to transfer skill and effective practice to all colleagues. The teacher-librarian promotes, models and empowers the success of all in making comprehension a school priority. We are now capitalizing upon a natural match between the information literacy goals of Information Power2 and the comprehension needs of the school. The notion that reading comprehension is tied to information literacies is relatively novel, since the two have been treated as nearly separate domains in the past, but we can no longer afford such an artificial separation. Literacy is about wrestling understanding from chunks of information, whether those chunks be numerical, textual, visual, cultural or artistic. Comprehension, on the other hand, has traditionally been more narrowly defined as the understanding of paragraphs and passages; but a marriage of the two seems well timed as the NCLB testing juggernaut thunders across the nation.3 Note: While this article was originally written for an American audience, the themes should resonate elsewhere as politicians in lands such as Australia toy with the idea of imitating the NCLB annual testing model and dream of imposing nationally-dictated educational systems on schools everywhere.

II. Every Teacher a Teacher of Comprehension Schools can no longer afford to relegate the teaching of reading comprehension to a handful of reading specialists. Nor can they rely on just a few nationally approved reading programs to deliver great test results. Reliance upon supposedly teacher-proof scripts is foolhardy, especially when seeking improvement in inferential reasoning and advanced comprehension. In one rarely publicized example, the Abell Foundation in Baltimore funded a five-year effort (The Baltimore Curriculum Project) to raise the performance in 18 elementary schools employing the much heralded and federally approved Direct Instruction approach to reading. Even though this program was “research-based,” the foundation admitted at the end of five years that results were disappointing.

Just because a program has worked in some places does not mean that we can predict or guarantee success, yet it is fashionable to suggest that research-based programs can be trusted to achieve results despite much evidence to the contrary. Zealous partisans promise much while failing to mention these programs' previous failures. As illustrated by the Abell Foundation experience above, packaged programs and silver bullets that seem attractive at first blush may disappoint in the long run. Authentic progress is usually hard won and stubbornly resistant to simple solutions and prescriptions. This is especially true when comprehension becomes a major component of the testing experience. Simple measures of very basic primary level goals often show impressive results unlikely to persist into the middle years. 5

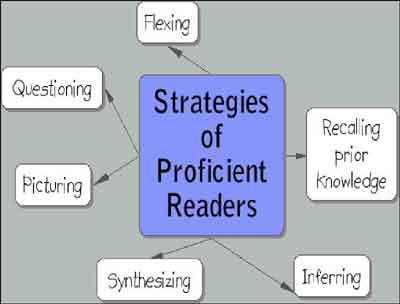

Research into effective practice indicates that achievement of strong scores on comprehension tests is possible, but progress will require teaming across all classrooms so that students spend some time in each hour of each day acquiring, practicing and sharpening essential comprehension skills such as questioning, picturing, inferring, recalling past knowledge, synthesizing and flexing.6

The teacher-librarian is a perfect choice to lead this effort, providing aid and comfort to the many classroom teachers who emerged from teacher preparation with only a course or two in the teaching of reading. As schools approach the huge task of building the capacity of every teacher to be a teacher of reading, the importance of the teacher-librarian is enhanced greatly. It was once enough to deliver a reading program as a part of language arts. That will no longer suffice. Reading comprehension and thinking must extend and penetrate into every nook and cranny of a school's program so that students learn to wrestle meaning from the most stubborn and resistant of sources across content areas. In some ways, launching an effective reading program for this decade is akin to the classic story of stone soup. We begin with a great idea, the dream of a wonderful soup, but is only when the entire community pitches in and adds something to the broth that the soup takes on character and value. III. The Prime Strategies If the teacher-librarian knows the six prime strategies and can help the rest of the staff to master and apply them in daily practice, the school can integrate these strategies into the classroom experience of all students. This article will present only brief summaries to clarify what is involved with each strategy but will offer a number of resources that serve effectively as study guides to support skill development by media specialists and classroom teachers. A. Questioning - A proficient reader employs a toolkit of questions in order to solve puzzles, unlock mysteries and fashion meaning when it is elusive. B. Picturing - A proficient reader relies upon her or his mind's eye to increase understanding and organize complex ideas. C. Inferring - A proficient reader can read between the lines, put clues together and figure out reasonable interpretations. D. Recalling Prior Knowledge - A proficient reader awakens relevant memories of information that might cast light on the topic or issue at hand. E. Synthesizing - A proficient reader is skilled at combining fragments and ideas in new ways so as to squeeze import and novelty from them. F. Flexing - A proficient reader knows how to slide back and forth across an array of strategies until one succeeds, picking and choosing purposefully.

IV. Acquiring the Skills Some teachers will spend several years acquiring, mastering and applying the repertoire of comprehension strategies outlined in this article. While the list above seems simple enough, the “classroom moves” required to translate theory into practice number in the thousands. The effective combination and delivery of tactics is a demanding task, and the skill acquisition is time consuming, frustrating and labor intensive. There are no slam dunks, no silver bullets and no simple recipes. Teachers face a complicated array of tactics and moves that must be combined effectively with other classroom moves so as to nurture learning while challenging students and making them feel successful. The process of acquiring and practicing these tactics might be called “stumbling toward competence” because it involves a considerable amount of trial-and-error experimentation and adaptation before success can be claimed.7 There is too little appreciation of adult learning strategies these days as current policy often promotes training models and the mastery of so-called teacher proof programs, but there is a substantial and well respected body of research that indicates that teachers must learn to do these complicated and important tasks in actual practice. It is not enough to sit, watch and take notes. They must acquire competence through trial.8 They thrive on support. They need organizational cultures that emphasize support and reduce risk. An example of a successful change model is the QUILT program9 which offers a model for how to advance the cause of comprehension”

Factory models of educational change may be trendy these days, but the pendulum is likely to swing back to an appreciation of change strategies that actually work. A savvy teacher-librarian knows how to straddle the fashionable and the classic, practicing enough of each to maintain credibility while waiting for true value to emerge. At the same time the teacher-librarian is straddling these trends, the teachers will be watching and waiting, wondering if “this too shall pass,” since they have seen fashions and the bandwagons come and go over the decades with little lasting impact. The teacher-librarian cannot be seen as a zealot or a true believer. Teachers must sense that the teacher-librarian is unaligned and completely practical in focus. Orthodoxy begets rebellion and resistance. V. The Teacher-Librarian as Professional Developer For a while now some of us have urged the teacher-librarian to take a leadership role in the provision of professional development. This expectation is clearly stated in “Beyond Proficiency: Essentials of a Distinguished Library Media Program” from the Kentucky Department of Education :

In respect to this job expectation, Kentucky goes farther than Information Power, which is relatively quiet about this leadership role, stressing partnership rather than leadership. But neither document is clear about professional development for reading comprehension, referring instead to technology and literacy as a prime focus. This article suggests that this linkage between traditional media center concerns and the teaching of reading represents a profound shift and a great opportunity. While “professional developer” may not have been a role many school librarians considered prime when first taking up their challenging assignments, the role offers much in the way of job satisfaction and value at a time when many library programs face the threat of down-sizing and cut backs. The teacher-librarian who stands at the forefront of school success is in a strong position to argue for sustained funding and program support. The following sections introduce methods to employ with colleagues to mobilize their support of improved reading comprehension across the school.

VI. Prime Strategy One - Questioning

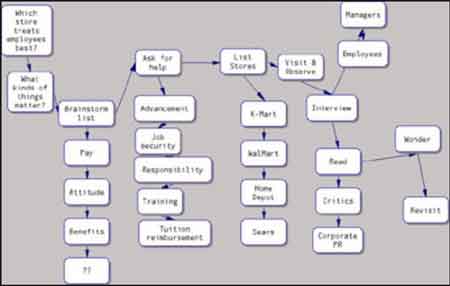

How can a school strengthen the questioning abilities of students in ways that enhance performance on tough comprehension questions? We must give students frequent guided practice until we see skills and independence flourish. Traditionally, we have not provided students with enough practice forming their own questions to figure out mysteries and puzzles. We have focused too much on single question/response pairs, with the teacher asking the questions and the student finding and spitting back answers. When answers are not directly stated, the reader must experiment with a series of questions until the answer can be developed. It is less about finding and uncovering than building. One pulls and tugs at the clues with questions. It is like untangling a snarled fishing line. Making sense out of nonsense. Creating meaning where none shines through. Each student needs a questioning toolkit - a conscious awareness of different types of questions and their differing functions. We teach students types of questions from the earliest age so they can reach into their toolkit or toolbox and grab a saw when they need a saw, a hammer when they need a hammer and a drill when they need a drill. As the old folk saying goes, if your only tool is a hammer, then every problem becomes a nail. How do we teach them this questioning process?

The teacher-librarian is in a great position to model these practices and to connect teachers with resources that will support growth in skill such as the following:

VI. Prime Strategy Two - Picturing How do we teach our students to make powerful use of their mind's eyes to support reading comprehension?

Click here to enlarge the above diagram. This picturing ability comes in handy when confronting reading selections on state tests that proceed for more than twenty paragraphs. For teacher practice examples go to http://www.questioning.org/tests/picturing.html VI. Prime Strategy Three - Inferring

Advanced comprehension challenges often require students to read between the lines and make meaning when none is directly stated. When they are clue-less, how do we teach our students to find what is missing or what is implied?

For practice examples go to http://www.questioning.org/tests/infer.html VII. Prime Strategy Four - Recalling Prior Knowledge

Effective pre-reading strategies involve awakening information and mental frameworks about a topic before starting the actually reading process. In technical terms this process is called activating schema - providing a context, some background and a structured way about receiving the new material. Instead of starting cold, the student has a receptive frame of mind. Memory often plays tricks on us. Much of what we already know lies hidden where it will do us little good when wrestling with a difficult comprehension passage, yet proficient readers are skilled at tapping into and reawakening these sources to cast light on whatever passages they are considering. As with the other strategies, this strategy can become second nature, an automatic step that young readers take when they are about to read a passage. Doing so depends upon the modeling and the practice provided by the teacher-librarian and the classroom teachers. VIII. Prime Strategy Five - Synthesizing

How do we teach our students to mix, match, combine and weave ideas into something new? Metaphors help make synthesis seem less abstract and elusive.

We give students practice with pairs of such tasks, asking how synthesis in one setting (cooking the omelet) might inspire good thinking about synthesis in writing. We give students practice with models that teach synthesis strategies such as SCAMPER (Eberle, 1997) and The Six Traits Approach to Writing - http://fnopress.com/start/mod8.html. We ask students to work on solving problems from their own times or from history, putting them in role playing situations that require them to investigate and propose smart ways of handling issues or challenges. We ask students to come up with new titles for stories, poems, paintings, songs, businesses or schools. We ask students to write ads, slogans, letters to the editor, complaint letters, jingles and songs. We ask students to express deep feelings with the help of the fine arts. For practice examples go to http://www.questioning.org/tests/synthesizing.html IX. Prime Strategy Six - Flexing Flexing is a term that captures what others mean by metacognition and strategic choice. The proficient reader knows how to shift gears, change directions, try something different and run through a host of strategies until meaning evolves. Versatility is paramount as the reader engages in trial-and-error experimentation until something works. Flexing stands in contrast with the currently fashionable approach to reading that emphasizes patterns and memory. An independent thinker is capable of strategizing, of digging deep into a repertoire of thinking tools to find the ones that will unlock the meaning of a difficult passage. How can we best develop such independence and an inclination toward strategic reading? Key to such growth is repeated and continuing exposure to surprising, thorny and highly challenging reading puzzles until the puzzling becomes commonplace rather than unsettling and threatening. This independence goal goes to the very essence of education. X. Partnering and Adding to the Comprehension Repertoire It takes years to acquire and practice a comprehensive repertoire of comprehension teaching strategies like those mentioned in this article. One way to support that learning process is to create a network of learners similar to the QUILT program mentioned earlier. Teachers work and learn in teams - communities of practice - as they consult practical guides11 to effective practice written by teachers with a track record of success. Many of the books listed below contain hundreds of strategies - tricks of the trade - each of which might require a week or more to learn and adapt to a teacher's classroom. The journey is a long but fruitful one. Notes 1. No Child Left Behind, the title assigned to the National Education Law, is now often referred to as NCLB. Some educators have applauded the law's emphasis on testing and accountability while others have been sharply critical of the change strategies embedded in NCLB's rules and regulations. See “NCLB: AKA "Helter-Skelter?" by Jamie McKenzie. http://nochildleft.com/2003/aug03aka.html. 2. Resources for Information Power can be found at the ALA Web site http://www.ala.org/ala/aasl/aaslproftools/informationpower/informationpower.htm. 3. NCLB eventually requires annual testing of all students at most grades, but only in math and reading at first. This has raised the stakes for many schools as they must demonstrate AYP (Acceptable Yearly Progress) on such tests for nine sub groups or be labeled as failing schools. 4. Source: http://www.abell.org/abellprograms/baltimore.html. 5. Many of the studies used by the National Reading Panel to promote a major emphasis on phonics were studies of small samples and brief duration that showed little connection between what was being measured and long term reading power or comprehension. Note the detailed critique in Reading the Naked Truth: Literacy, Legislation and Lies by Gerald Coles (Heinemann, 2003). 6. P. David Pearson in his research on reading comprehension in the 1980s identified strategies of proficient readers - work cited by Stephanie Harvey in Nonfiction Matters: Reading, Writing and Research in Grades 3-8. More recently, Pearson has combined with others to determine which approaches to change have the most impact “on schools with populations of students at risk of failure by virtue of poverty.” Teaching Reading: Effective Schools, Accomplished Teachers. Edited by Barbara M. Taylor and P. David Pearson. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, New Jersey, 2002. Chapter 16 - “Research-Supported Characteristics of Teachers and Schools that Promote Reading Achievement” - is particularly relevant to the thrust of this article. 7. McKenzie has written extensively of this learning process in an online article, “Quality Teaching: From Theory into Practice” in The Question Mark, Vol. 1 No. 2 September 2004. http://questioning.org/sep04/qt.html 8. Joyce and Showers have documented the successful teacher change process over several decades of field studies that demonstrated that skill acquisition thrives when peer coaching and support systems are in place to encourage risk taking. Showers, Beverly & Joyce, Bruce “The Evolution of Peer Coaching” in Educational Leadership, March, 1996. 9. Questioning and Understanding To Improve Learning and Thinking - A Program Designed To Enhance Student Learning by Improving Teachers' Classroom Questioning Techniques. Developed and tested by the Appalachia Educational Laboratory (AEL) http://www.ed.gov/pubs/triedandtrue/quest.html 10. “Beyond Proficiency” is available as a PDF file at http://www.education.ky.gov/KDE/Instructional+Resources/Curriculum+Documents 11. Suggested guides for teachers to develop a comprehension repertoire are: ----- Primary Grades ----- Mosaic of Thought : Teaching Comprehension in a Reader's Workshop by Susan Zimmermann, Ellin Oliver Keene, Heinemann, 1997. ----- Intermediate and Middle Grades ----- Strategies That Work: Teaching Comprehension to Enhance Understanding. Stephanie Harvey, Anne Goudvis. Stenhouse Publishers, 2000. Nonfiction Matters: Reading, Writing, and Research in Grades 3-8. Stephanie Harvey, Stenhouse Publishers, 1998. ----- Secondary Students ----- I Read It, but I Don't Get It: Comprehension Strategies for Adolescent Readers. Cris Tovani, Stenhouse Publishers, 2000.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Credits: The photographs were shot by Jamie McKenzie. |

From Now On

From Now On