fno.org

|

|

| Vol 20|No 3|January 2011 | |

| Please feel free to e-mail this article to a friend, a principal, a parent, a colleague, a teacher librarian, a college professor, a poet, a magician, a vendor, an artist, a juggler, a student, a news reporter or to anyone else you think might enjoy it. | |

Combating Mental Brownout in the Classroomby Jeff King, Ed.D. Director, Koehler Center for Teaching Excellence Texas Christian University

|

|

| The one-page (front and back) PDF document accompanying this article has an interesting history here at Texas Christian University. As at most colleges and universities (as well as in high schools, middle schools, and even these days, many elementary schools), our faculty were struggling with the issue of electronic distractions directing their students' focus in class away from course content. |

Above classroom is from Texas Christian University |

|

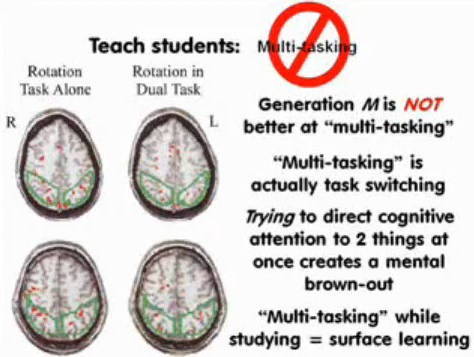

You know the scenarios: Courtney brings her iPhone to class and spends half the time texting her friends. Bryan brings his laptop and plays fantasy football. We had a student on a panel at our recent new faculty orientation say that he took a course here in which one of his classmates watched horse videos on her laptop the entire time in every class. Our faculty were convinced that such divided attention just couldn't be good for learning. Turns out they were right. Research shows that "paying attention" to more than one thing at a time results in a '"mental brownout" — decreased brain power allocated to either of the two things than the brain power available when focusing on a single task or topic. The problem is that students believe they can multitask. They've been told all their lives that they're good at it.

Further, studying at home is commonly done in a highly multitasked environment, so '"normal'" studying is, by definition for much of Generation M, studying done while you're also: a) on your cell phone, b) on your laptop with windows open that have nothing to do with what you're studying (Facebook, Twitter — the list goes on), c) watching TV or videos, d) playing computer/video games, or e) all of the above. A New York Times article of a few years back included a picture of a 16-year-old student working on his homework, which was writing an English paper. He was simultaneously practicing licks on his guitar, surfing the web, and texting on his cellphone . . . while he was writing his English paper. Was that English paper the same quality as it would have been had he been '"monotasking'"? The research says no, and our faculty wanted some way to help students understand this when they had the discussion at the start of the semester about why they were banning laptops from the classroom. (Except, of course, for students with documented disabilities-related needs.) I suspect faculty wanted more substantiation than simply telling students multitasking is not good for learning. With a positive emotional environment necessary for optimal learning, it's easy to see that, '"Because I said so,'" is not the best of strategies. In fact, students are resentful when they're not allowed to multitask. The excellent '"Digital Nation'" episode of Frontline includes a clip of an M.I.T. student stating flatly that faculty need to accept that today's students are completely capable of multitasking and that it's unfair to restrict that activity. In other words, faculty '"just need to get over themselves.'" Contributing to this student belief is their past performance. It is a sad truth that in many places, pre-college (and even undergraduate college) education in America revolves around successful memorization of material which is reproduced on a test. In that kind of environment, successful memorization must be valued; remembering the information later or using the information to conteptualize and hypothesize, for example, need not be valued. So when a professor says, '"No multitasking,'" but a student has a history of 4.0 performance during K-12 while happily multitasking throughout, something doesn't ring true. There's a lot of food for thought about that, but here's a key point about multitasking: It engages precisely that portion of the brain that is good at learning repetitive tasks like memorization, a famously "surface learning" technique, yet college demands (or should demand) "deep learning" — the kind of learning in which students must contextualize, follow narrative threads, build and defend arguments, etc. (Not that you don't also need good surface learning skills — you and I both will request a surgeon doing our brain surgeries who has successfully memorized the location of the twelve cranial nerves.) So faculty needed help in explaining the following things to students: • Why it hurts learning if you're multitasking. • Why past success in school doesn't necessarily transfer to a learning environment which requires focused attention. • Why focusing and paying attention — really paying attention — is a needed skill for college success. Thus was born the one-page handout. Faculty have reported that it helps them explain their no-laptop decisions more effectively to students. The impact of the handout is heightened, I believe, when faculty use the following activity to drive home one of the points made in the document. (This activity is something done in each class taught by one of the researchers quoted in the handout, Dr. David Meyer at the University of Michigan). Time the group of students as they count from one to ten. Time them saying the letters of the alphabet A to J. Then time them saying the first number followed by the first letter, then second number followed by second letter, etc. Meyer's students do the first two tasks in around two seconds. The third task can take upwards of 20 seconds (for those students who don't give up in fits of laughter beforehand). The point? If you truly could multitask, then you should take only four seconds to accomplish the third task. It's a great demonstration of a key fact about human education: You can't learn what you don't pay attention to. |

|

|

Copyright Policy: Materials published in From Now On may be duplicated in hard copy format if unchanged in format and content for educational, nonprofit school district and university use only and may also be sent from person to person by e-mail. This copyright statement must be included. All other uses, transmissions and duplications are prohibited unless permission is granted expressly. Showing these pages remotely through frames is not permitted. |

|

Outline of chapters and description of book available here.

Order your copy of The Media Literacy Toolbo— from the FNO Store