|

|

Vol 9|No 9|May|2000 |

|

©2000 JMcKenzie

Beyond Information Power

by Jamie McKenzie

about the author

Who Owns the Knowledge Economy?

Lead story in the April 8, 2000 issue of The Economist

An interesting question.

Many times, we discover that information is just not enough. Sometimes we find even that answers are not enough. We may stumble over wrong answers or wade through answers to wrong questions.

The more important the question - a matter of life or death - a moral dilemma - a conundrum - the more elusive the answers and the less satisfying and sufficient the pat answers and prescriptions readily available.

To prepare young people for these essential questions, we must take them beyond the quest for information and answers. We must show them how to build their own answers, to fashion insight out of the bits, bytes and pieces that come streaming onto desktops in this increasingly digital world, to relate what they have learned to their own particular needs, preferences and beliefs. We must teach them to develop fresh ideas.

It may be that neither information nor literacy will take us far enough unless literacy means more than interpreting and understanding information. We must be able to move past literacy to focus on the uses of knowledge as applied to our own particular challenges and choices.

We cannot rely upon clip art and template thinking.

When struggling with the essential questions and decisions of life, we often grapple with mountains of information, much of it conflicting, much of it misleading, much of it distorted and much of it confusing.

The search for insight and understanding may be hampered by the noise and volume of information available.

Wise choices take inventive skill. Collecting, gathering and hunting are just preliminaries.

But most models of research for schools devote too little attention to this invention process. Most models still countenance the gathering of other people's best thoughts. They are tilted toward the harvesting of conventional wisdom. They may leave us prisoners of middle people and thinking that sticks right down the middle of the road.

We may look to artists like Georgia O'Keeffe and Wassily Kandinsky or to engineers like Jim Clark (founder of Silicon Graphics, Netscape and Healtheon) to teach us about inventive thinking.

Quoting from Wassily Kandinsky writing in Concerning The Spiritual in Art

©JMcKenzie

The artist must be blind to distinctions between "recognized" or "unrecognized" conventions of form, deaf to the transitory teaching and demands of his particular age.

Examples of Kandinsky's work at the Web Museum

All means are sacred which are called for by the inner need. All means are sinful which obscure that inner need.

Color is the keyboard, the eyes are the harmonies, the soul is the piano with many strings. The artist is the hand that plays, touching one key or another, to cause vibrations in the soul.

He must watch only the trend of the inner need, and harken to its words alone. Then he will with safety employ means both sanctioned and forbidden by his contemporaries.

P. 35

Which treatment is best for my own particular case of prostate or breast cancer?

As this article was drafted, the Mayor of New York announced his diagnosis of prostate cancer and began his search for a treatment.

©Photosphere

One doctor may call surgery "the gold standard" while another might argue that surgery is "past its prime."

Which do we believe?

©Photosphere

One doctor claims a low recurrence rate for surgery while another cites a study reporting twice the risk.

Which do we believe?

Should we select surgery? radioactive seeds? hormonal blockade? watchful waiting?

Many of life's most important decisions prove remarkably frustrating despite our best efforts to proceed beyond information to understanding. Medical choices can prove especially thorny as Jerome Groopman, MD dramatically illustrates in Second Opinions: Stories of Intuition and Choice in the Changing World of Medicine (Penguin, Putnam, New York, 2000).

Groopman's stories describe patients, families and physicians struggling with the often baffling gray areas of medicine where science meets its limits and something more is needed. In some of the stories, the patient must contend with advice that is dangerous, doctors who are not responsive and HMOs constricting options. He argues that we must look for physicians who are caring as well as skilled, medical advisers who can also be our advocates as we try to find our way through the system.

In the opening story, Groopman and his wife, also a doctor, almost lose their baby son because an emergency room doctor advises them to delay a procedure until the next day. The book is disturbing but ultimately empowering. On the one hand we learn the dangers of relying too heavily on experts. On the other hand we see patients and physicians teaming effectively to solve mysteries and restore good health.

©Photosphere

People adapt differently, physically and emotionally, to each illness and react in varying ways to a given therapy. This means that diagnosis and treatment cannot be strictly bound by generic recipes, but must be made individual to be consistent with the particular clinical and psychological characteristics of the individual.

Second Opinions, Page 7

Groopman's point might also apply to students, teachers and learning. Even though generic recipes and routines rarely create the best circumstances for classrooms, there are always plenty of cookbook solutions in the offing. Good teachers know that learning is most apt to occur when they have particularized and customized the lessons (see "Strategic Teaching" - FNO, December, 1998)

Fresh Solutions to Old Problems

Conventional wisdom is rarely sufficient to handle the problems that have stayed with us for decades. If conventional wisdom were enough to bring back endangered species, for example, they would no longer be listed.

EPA says dams on Snake River must come down to save salmon

Story by Robert McClure in Seattle Post-Intelligencer

April 29, 2000

McClure reports that the Army Corps of Engineers has issued a study stating that dams may be good for salmon by keeping the temperature of the water down. The EPA (Environmental Protection Agency) responsible for protecting the Snake River salmon under the Endangered Species Act "attacked the Corps' scientific conclusions as false and misleading." according to McClure.

In this case, possessing information is not enough to formulate effective policy. Different folks with different interests may see and interpret the same facts differently.

Farmers? Loggers? Commercial Fishers? Sports Fishers? Conservationists? Utilities? Homeowners? Politicians?

Students?

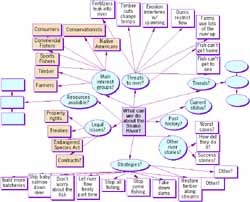

Can we teach our students to make effective use of cluster diagrams to map out the complexity of these types of issues and questions?

Once they have their maps, what next? How do we teach them to weigh the consequences of pulling down the dams or not pulling down the dams?

Can fish sometimes be more important than people?

Is compromise a reasonable response to an environmental challenge?

What are the limits to reason? to logic?

When we raise young people to cut and paste the best thinking of their elders, we short change them. New thinkers should amplify and improve upon the insights of their sages, heeding wisdom that has survived the tests of time and the vagaries of fashion.

We remind them that one person's "sage" may be another person's "bureaucrat."

Once they know conventional wisdom, they must ask "What next? How do we push into new territory? How could we make this better? What did they miss? What can we add?"

As we saw in the article about the Snake River dams and salmon, the elders often disagree over the facts and the implications of the facts. Knowing the facts is not the same as understanding what to do. Young people will require more than information to develop wise strategies.

Fresh Solutions to New Problems

Conventional wisdom is especially weak when we face brand new problems unlike any seen before. For several decades we have heard warnings that the rate of change sweeping through our economy and society requires a workforce with flexibility, resourcefulness and imagination. Proceeding on autopilot is not an option. These are times that demand new thinking.

In 1991, a From Now On article called for a generation of students with "a change ethic."

How do we raise a generation with a change ethic?

- We make change and surprise constant elements in our classrooms.

- We attack routine and humdrum with adventure, inquiry and investigation.

- We ask students to wrestle with essential questions to awaken curiosity and provoke learning.

- We invite students to make meaning out of chaos and nonsense.

- We replace the ho hum routines of Industrial Age textbooks, ditto sheets and fill-in-the-blanks learning with problems, challenges and issues drawn from the "real world."

- We open up schools so that the world is the classroom instead of the classroom being the world.

- We create a change ethic by offering students a "real time," authentic education in "real time" schools.

In 1992, a From Now On article suggested that we need students who can be "everyday heroes"

If successful, we will raise a generation of students who can find their own way through the labyrinth of modern society, constructing meanings from the complex data that swirl around us during this Age of Information, a generation of "everyday heroes" intent on using their insights to make this a better world, slaying, converting, enlisting or taming whatever dragons or Minotaurs may impede their progress.

The Hero as Creator

Catford and Ray draw a close parallel between the stages of the hero's journey and the six stages of the creative process (preparation, frustration, incubation, strategizing, illumination and verification (pages 24-27).

In order to be successful during these six stages, they maintain that a creative hero needs the following four "magic" tools:

1) Having faith in your creativity

Because the journey will almost necessarily plunge you into darkness at various times, faith becomes essential. During those long time periods answers and solutions prove evasive, the technology wizard must believe that perseverance will pay off, that clarity will come, that some kind of answer will arise out of the confusion and darkness. A lack of faith will translate into a lack of courage and a tendency to play it safe, keeping close to home and sticking with what is familiar and reassuring.

2) Suspending negative judgment

Because negative judgments virtually shut down creative production, the technology wizard drives away doubt and criticism, especially during the exploration and idea generation stages. The goal is to open one's mind to possibilities never before considered. If you find a judge perched upon your shoulder critiquing every new thought, banish the boring gremlin and invite your clown to takes its place. This is a time for playful consideration of intriguing futures.

3) Practicing precise observation

A visit to unfamiliar territory places a premium on careful observation. One cannot rely upon previous experience and knowledge for guidance. The creative hero slows down activity, emphasizes reflection and seeks understanding.

4) Asking penetrating questions

Precise observation relies upon penetrating questions, for good questions are the tools we use to develop insight when encountering new and strange environments or experiences. Questions bring us out of the darkness and into the light. They probe negative space and help us to make meaning.

Adapted from Catford and Ray's The Path of the Everyday Hero

Whether you call it problem-based learning, project-based learning, engaged learning or constructivist learning, our students will only come to thrive in this new information landscape if we engage them frequently in challenges calling for fresh thought.

The alternative is unthinkable . . .

MentalSoftness™

Unless we take care to develop the foundations for rigorous independent thought, we risk raising a generation of young people inclined to accept the sound bites, mind bytes, eye candy and mind candy so typical of the new information landscape. There are, after all, millions being spent on marketing to shape the thinking of consumers and citizens. Misinformation and infotainment are rampant, with simple answers to complex questions appearing like the dandelions of spring - bright, appealing, widespread and persistent.

Amid complaints of a new plagiarism and much glib thinking, we must keep a watch for the following indicators of MentalSoftness™ - the product of lazy thinking, intellectual channel surfing and the entertainerizing of knowledge work.

Prime Indicators of MentalSoftness™

Fondness for clichés and clichéd thinking - simple statements that are time worn, familiar and likely to carry surface appeal.

Fondness for clichés and clichéd thinking - simple statements that are time worn, familiar and likely to carry surface appeal.

Reliance upon maxims - truisms, platitudes, banalities and hackneyed sayings - to handle demanding, complex situations requiring deep thought and careful consideration.

Reliance upon maxims - truisms, platitudes, banalities and hackneyed sayings - to handle demanding, complex situations requiring deep thought and careful consideration.

Appetite for bromides - the quick fix, the easy answer, the sugar coated pill, the great escape, the short cut, the template, the cheat sheet.

Appetite for bromides - the quick fix, the easy answer, the sugar coated pill, the great escape, the short cut, the template, the cheat sheet.

Preference for platitudes, near truths, slogans, jingles, catch phrases and buzzwords.

Preference for platitudes, near truths, slogans, jingles, catch phrases and buzzwords.

Vulnerability to propaganda, demagoguery and mass movements based on appeals to emotions, fears and prejudice.

Vulnerability to propaganda, demagoguery and mass movements based on appeals to emotions, fears and prejudice.

Impatience with thorough and dispassionate analysis.

Impatience with thorough and dispassionate analysis.

Eagerness to join some crowd or other - wear, do and think what is fashionable, cool, hip, fab, or the opposite or whatever . . .

Eagerness to join some crowd or other - wear, do and think what is fashionable, cool, hip, fab, or the opposite or whatever . . .

Hunger for vivid and dramatic packaging.

Hunger for vivid and dramatic packaging.

Fascination with the story, the play, the drama, the show, the episode and the epic rather than the idea, the question, the argument, the premise, the logic or the substance. We're not talking good stories or story lines here. We're talking pulp fiction.

Fascination with the story, the play, the drama, the show, the episode and the epic rather than the idea, the question, the argument, the premise, the logic or the substance. We're not talking good stories or story lines here. We're talking pulp fiction.

Fascination with cults, personalities, celebrities, chat, gossip, hype, speculation, buzz and blather.

Fascination with cults, personalities, celebrities, chat, gossip, hype, speculation, buzz and blather.

Strategies for Finding Essential Questions

Essential questions are embedded within the curriculum if we know how to look for them. One strategy is to combine certain sentence stems with the specific material being studied. But there is always the danger of becoming formulaic. The exploration of any important issue usually requires the framing of many subsidiary questions especially suited to the particular question at hand.

1. What can we do about . . . (problem solving and decision making)

"What can we do about the Snake River?" is quite different from "What can we do about the Snake River dams?" or "What can we do about the Columbia River dams?" and both of those may be quite different from "What can we do about the water needs of farmers or salmon counting upon those rivers?"

Move the questions to Canada . . .

"What can we do about the Fraser River?"

Shift the question by replacing "can" with "should."

"What should we do about our river?" Now we are requiring ethical literacy.

Add the dimension of role playing.

"If you are a Native American living along the Snake wanting to preserve fish related tribal traditions, what do you think we should do about the river?"

"If you are a commercial fishing captain living along the Snake wanting to earn enough from fishing to support your family, what do you think we should do about the river?"

Click on the picture to see it full size. (Very large graphic file.)

Download a demonstration copy of Inspiration™ from this site.

We begin to see that questions are as unique as snowflakes, each suggesting distinct and intricate patterns of related questions.

One good question may spawn hundreds of subsidiary questions, and the ability of the thinker to move beyond mere information to understanding is fundamentally related to the skill with which the thinker can generate and then explore such questions.

What can we do about . . .

If you were making recommendations to your government to address one of the following problems, what would be the five most important steps you would urge? Why?

- acid rain

- global warming

- urban decay

- violent crime

- drunken driving

- smog

- traffic congestion

- water pollution

- declining fish harvests

- endangered species

- unemployment

- government corruption

- health care costs

- AIDS

- teen pregnancy

- school drop out rates

- school shootings

- racial conflict

- gangs

- access to information on the Internet

- privacy of information on the Internet

- Social Security

- campaign finance

2. Which is best?

Comparisons can provoke and require fresh thinking, as was fully demonstrated in the October, 1999 issue of FNO, "Students in Resonance." (see article)

When we compare the dialogue of three playwrights, the properties of three chemicals, the cultures of three cities or the attributes of any collection of people, places, objects, ideas or experiences, our students are less likely to simply collect an answer or cut and paste the thinking of others.

From "Students in Resonance"

When we set two or more ideas, paintings, poems, leaders or cities side by side, we provoke thought and comparison.

- idea vs. idea

- beach vs. mountain

- painting vs. painting

- road vs. track

- poem vs. poem

- leader vs. leader

- digital vs. analog

- city vs. city

- writer vs. writer

- freedom vs. license

- browser vs. browser

- cola vs. cola

- cafe vs. cafe

- trend vs. fad

- bar vs. bistro

- investment vs. scheme

- proposal vs. proposal

- suitor vs. suitor

- Internet stock vs. Fortune 500

-

When we place them thus in juxtaposition, we set in motion thoughts of difference - cognitive dissonance. The sharper the contrast, the greater the dissonance. We can feel the vibration, the conflict, the discomfort.

We are thrown off balance. Our minds are intrigued . . . our curiosities awakened. We want to resolve the dissonance . . . bring things back into harmony or resonance.

Too much school research and thought has suffered from a singular focus. Topical research (Go find out about California!) lacks the energy and excitement of comparison and choice.

- Which city should we move to?

- Which job shall we take?

- Which neighborhood will make us happy?

- Which roommate will endure beyond the first month?

3. What do you suppose will happen?

Scenario building is a premier skill for changing times - looking ahead thoughtfully to consider what is likely to happen under various circumstances - making reasonable predictions based on careful analysis of trends, forces, variables and key factors.

We engage students in generating, then testing hypotheses about possible and desirable futures. But we also require them to provide a foundation for these hypotheses.

"Why do you suppose that will happen? How do you know? What evidence can you provide?'

This is no simple matter of reading Tarot cards, tea leaves or chicken bones. Looking around Time's corner is an essential skill requiring a mixture of logic and intuition.

Fighting MentalSoftness™ and Mental Flab

The main strategy to fight current trends toward MentalSoftness™ and Mental Flab is for schools to offer mental exercise programs. Frequent practice on demanding questions will build up the mental stamina and conditioning to support sustained inquiry and investigations. (see "Scoring High" in the April. 1999 issue of FNO)

This strategy is no bromide. No quick fix. In some schools it may require some painful shifting of past practice and rituals. Old fashioned approaches to school research tended to be infrequent and peripheral. They rarely built thinking skills or required innovative thinking. In too many cases they were more like spectator sports.

Moving to a more demanding model will require a substantial investment (15-30 hours annually) in professional development that engages teachers in the same kinds of demanding research experiences we hope to see them demand of their students.

Just as no one develops stamina by watching others run up and down a basketball court, students will not learn to think for themselves by cutting and pasting the thinking of others.

"Thought by association" is an unproven notion.

Credits: The photographs were shot by Jamie McKenzie.

Some of the icons are courtesy of Jay Boersma's site

(http://www.ECNet.Net/users/gas52r0/Jay/home.html).

Copyright Policy: Materials published in From Now On may be duplicated in hard copy format if unchanged in format and content for educational, nonprofit school district and university use only and may also be sent from person to person by e-mail. This copyright statement must be included. All other uses, transmissions and duplications are prohibited unless permission is granted expressly. Showing these pages remotely through frames is not permitted.

FNO is applying for formal copyright registration for articles.

|

©2000 JMcKenzie

|

Beyond Information Power

by Jamie McKenzie Lead story in the April 8, 2000 issue of The Economist An interesting question. |

Many times, we discover that information is just not enough. Sometimes we find even that answers are not enough. We may stumble over wrong answers or wade through answers to wrong questions.

The more important the question - a matter of life or death - a moral dilemma - a conundrum - the more elusive the answers and the less satisfying and sufficient the pat answers and prescriptions readily available.

To prepare young people for these essential questions, we must take them beyond the quest for information and answers. We must show them how to build their own answers, to fashion insight out of the bits, bytes and pieces that come streaming onto desktops in this increasingly digital world, to relate what they have learned to their own particular needs, preferences and beliefs. We must teach them to develop fresh ideas.

It may be that neither information nor literacy will take us far enough unless literacy means more than interpreting and understanding information. We must be able to move past literacy to focus on the uses of knowledge as applied to our own particular challenges and choices.

We cannot rely upon clip art and template thinking.

|

When struggling with the essential questions and decisions of life, we often grapple with mountains of information, much of it conflicting, much of it misleading, much of it distorted and much of it confusing.

The search for insight and understanding may be hampered by the noise and volume of information available. Wise choices take inventive skill. Collecting, gathering and hunting are just preliminaries. But most models of research for schools devote too little attention to this invention process. Most models still countenance the gathering of other people's best thoughts. They are tilted toward the harvesting of conventional wisdom. They may leave us prisoners of middle people and thinking that sticks right down the middle of the road. We may look to artists like Georgia O'Keeffe and Wassily Kandinsky or to engineers like Jim Clark (founder of Silicon Graphics, Netscape and Healtheon) to teach us about inventive thinking.

|

Which treatment is best for my own particular case of prostate or breast cancer?

As this article was drafted, the Mayor of New York announced his diagnosis of prostate cancer and began his search for a treatment.

One doctor may call surgery "the gold standard" while another might argue that surgery is "past its prime." Which do we believe?

One doctor claims a low recurrence rate for surgery while another cites a study reporting twice the risk. Which do we believe? Should we select surgery? radioactive seeds? hormonal blockade? watchful waiting? |

Many of life's most important decisions prove remarkably frustrating despite our best efforts to proceed beyond information to understanding. Medical choices can prove especially thorny as Jerome Groopman, MD dramatically illustrates in Second Opinions: Stories of Intuition and Choice in the Changing World of Medicine (Penguin, Putnam, New York, 2000).

Groopman's stories describe patients, families and physicians struggling with the often baffling gray areas of medicine where science meets its limits and something more is needed. In some of the stories, the patient must contend with advice that is dangerous, doctors who are not responsive and HMOs constricting options. He argues that we must look for physicians who are caring as well as skilled, medical advisers who can also be our advocates as we try to find our way through the system.

In the opening story, Groopman and his wife, also a doctor, almost lose their baby son because an emergency room doctor advises them to delay a procedure until the next day. The book is disturbing but ultimately empowering. On the one hand we learn the dangers of relying too heavily on experts. On the other hand we see patients and physicians teaming effectively to solve mysteries and restore good health.

|

|

People adapt differently, physically and emotionally, to each illness and react in varying ways to a given therapy. This means that diagnosis and treatment cannot be strictly bound by generic recipes, but must be made individual to be consistent with the particular clinical and psychological characteristics of the individual.

Second Opinions, Page 7 |

Groopman's point might also apply to students, teachers and learning. Even though generic recipes and routines rarely create the best circumstances for classrooms, there are always plenty of cookbook solutions in the offing. Good teachers know that learning is most apt to occur when they have particularized and customized the lessons (see "Strategic Teaching" - FNO, December, 1998)

Fresh Solutions to Old Problems

Conventional wisdom is rarely sufficient to handle the problems that have stayed with us for decades. If conventional wisdom were enough to bring back endangered species, for example, they would no longer be listed.

EPA says dams on Snake River must come down to save salmon

Story by Robert McClure in Seattle Post-Intelligencer McClure reports that the Army Corps of Engineers has issued a study stating that dams may be good for salmon by keeping the temperature of the water down. The EPA (Environmental Protection Agency) responsible for protecting the Snake River salmon under the Endangered Species Act "attacked the Corps' scientific conclusions as false and misleading." according to McClure. |

In this case, possessing information is not enough to formulate effective policy. Different folks with different interests may see and interpret the same facts differently. Farmers? Loggers? Commercial Fishers? Sports Fishers? Conservationists? Utilities? Homeowners? Politicians? Students? |

|

|

Can we teach our students to make effective use of cluster diagrams to map out the complexity of these types of issues and questions? Once they have their maps, what next? How do we teach them to weigh the consequences of pulling down the dams or not pulling down the dams? Can fish sometimes be more important than people? Is compromise a reasonable response to an environmental challenge? What are the limits to reason? to logic?

|

When we raise young people to cut and paste the best thinking of their elders, we short change them. New thinkers should amplify and improve upon the insights of their sages, heeding wisdom that has survived the tests of time and the vagaries of fashion.

We remind them that one person's "sage" may be another person's "bureaucrat."

Once they know conventional wisdom, they must ask "What next? How do we push into new territory? How could we make this better? What did they miss? What can we add?"

As we saw in the article about the Snake River dams and salmon, the elders often disagree over the facts and the implications of the facts. Knowing the facts is not the same as understanding what to do. Young people will require more than information to develop wise strategies.

Fresh Solutions to New Problems

Conventional wisdom is especially weak when we face brand new problems unlike any seen before. For several decades we have heard warnings that the rate of change sweeping through our economy and society requires a workforce with flexibility, resourcefulness and imagination. Proceeding on autopilot is not an option. These are times that demand new thinking.

In 1991, a From Now On article called for a generation of students with "a change ethic."

|

How do we raise a generation with a change ethic?

|

In 1992, a From Now On article suggested that we need students who can be "everyday heroes"

|

If successful, we will raise a generation of students who can find their own way through the labyrinth of modern society, constructing meanings from the complex data that swirl around us during this Age of Information, a generation of "everyday heroes" intent on using their insights to make this a better world, slaying, converting, enlisting or taming whatever dragons or Minotaurs may impede their progress.

The Hero as CreatorCatford and Ray draw a close parallel between the stages of the hero's journey and the six stages of the creative process (preparation, frustration, incubation, strategizing, illumination and verification (pages 24-27). In order to be successful during these six stages, they maintain that a creative hero needs the following four "magic" tools: 1) Having faith in your creativity Because the journey will almost necessarily plunge you into darkness at various times, faith becomes essential. During those long time periods answers and solutions prove evasive, the technology wizard must believe that perseverance will pay off, that clarity will come, that some kind of answer will arise out of the confusion and darkness. A lack of faith will translate into a lack of courage and a tendency to play it safe, keeping close to home and sticking with what is familiar and reassuring. 2) Suspending negative judgment Because negative judgments virtually shut down creative production, the technology wizard drives away doubt and criticism, especially during the exploration and idea generation stages. The goal is to open one's mind to possibilities never before considered. If you find a judge perched upon your shoulder critiquing every new thought, banish the boring gremlin and invite your clown to takes its place. This is a time for playful consideration of intriguing futures. 3) Practicing precise observation A visit to unfamiliar territory places a premium on careful observation. One cannot rely upon previous experience and knowledge for guidance. The creative hero slows down activity, emphasizes reflection and seeks understanding. 4) Asking penetrating questions Precise observation relies upon penetrating questions, for good questions are the tools we use to develop insight when encountering new and strange environments or experiences. Questions bring us out of the darkness and into the light. They probe negative space and help us to make meaning. Adapted from Catford and Ray's The Path of the Everyday Hero

|

Whether you call it problem-based learning, project-based learning, engaged learning or constructivist learning, our students will only come to thrive in this new information landscape if we engage them frequently in challenges calling for fresh thought.

The alternative is unthinkable . . .

MentalSoftness™

Unless we take care to develop the foundations for rigorous independent thought, we risk raising a generation of young people inclined to accept the sound bites, mind bytes, eye candy and mind candy so typical of the new information landscape. There are, after all, millions being spent on marketing to shape the thinking of consumers and citizens. Misinformation and infotainment are rampant, with simple answers to complex questions appearing like the dandelions of spring - bright, appealing, widespread and persistent.

Amid complaints of a new plagiarism and much glib thinking, we must keep a watch for the following indicators of MentalSoftness™ - the product of lazy thinking, intellectual channel surfing and the entertainerizing of knowledge work.

Prime Indicators of MentalSoftness™ |

Strategies for Finding Essential Questions

Essential questions are embedded within the curriculum if we know how to look for them. One strategy is to combine certain sentence stems with the specific material being studied. But there is always the danger of becoming formulaic. The exploration of any important issue usually requires the framing of many subsidiary questions especially suited to the particular question at hand.

1. What can we do about . . . (problem solving and decision making)

"What can we do about the Snake River?" is quite different from "What can we do about the Snake River dams?" or "What can we do about the Columbia River dams?" and both of those may be quite different from "What can we do about the water needs of farmers or salmon counting upon those rivers?"

Move the questions to Canada . . .

"What can we do about the Fraser River?"

Shift the question by replacing "can" with "should."

"What should we do about our river?" Now we are requiring ethical literacy.

Add the dimension of role playing.

"If you are a Native American living along the Snake wanting to preserve fish related tribal traditions, what do you think we should do about the river?"

"If you are a commercial fishing captain living along the Snake wanting to earn enough from fishing to support your family, what do you think we should do about the river?"

|

Click on the picture to see it full size. (Very large graphic file.) Download a demonstration copy of Inspiration™ from this site. |

We begin to see that questions are as unique as snowflakes, each suggesting distinct and intricate patterns of related questions.

One good question may spawn hundreds of subsidiary questions, and the ability of the thinker to move beyond mere information to understanding is fundamentally related to the skill with which the thinker can generate and then explore such questions.

|

|

What can we do about . . . |

If you were making recommendations to your government to address one of the following problems, what would be the five most important steps you would urge? Why?

|

2. Which is best?

Comparisons can provoke and require fresh thinking, as was fully demonstrated in the October, 1999 issue of FNO, "Students in Resonance." (see article)

When we compare the dialogue of three playwrights, the properties of three chemicals, the cultures of three cities or the attributes of any collection of people, places, objects, ideas or experiences, our students are less likely to simply collect an answer or cut and paste the thinking of others.

|

When we set two or more ideas, paintings, poems, leaders or cities side by side, we provoke thought and comparison.

When we place them thus in juxtaposition, we set in motion thoughts of difference - cognitive dissonance. The sharper the contrast, the greater the dissonance. We can feel the vibration, the conflict, the discomfort. We are thrown off balance. Our minds are intrigued . . . our curiosities awakened. We want to resolve the dissonance . . . bring things back into harmony or resonance. Too much school research and thought has suffered from a singular focus. Topical research (Go find out about California!) lacks the energy and excitement of comparison and choice.

|

3. What do you suppose will happen?

Scenario building is a premier skill for changing times - looking ahead thoughtfully to consider what is likely to happen under various circumstances - making reasonable predictions based on careful analysis of trends, forces, variables and key factors.

We engage students in generating, then testing hypotheses about possible and desirable futures. But we also require them to provide a foundation for these hypotheses.

"Why do you suppose that will happen? How do you know? What evidence can you provide?'

This is no simple matter of reading Tarot cards, tea leaves or chicken bones. Looking around Time's corner is an essential skill requiring a mixture of logic and intuition.

Fighting MentalSoftness™ and Mental Flab

The main strategy to fight current trends toward MentalSoftness™ and Mental Flab is for schools to offer mental exercise programs. Frequent practice on demanding questions will build up the mental stamina and conditioning to support sustained inquiry and investigations. (see "Scoring High" in the April. 1999 issue of FNO)

This strategy is no bromide. No quick fix. In some schools it may require some painful shifting of past practice and rituals. Old fashioned approaches to school research tended to be infrequent and peripheral. They rarely built thinking skills or required innovative thinking. In too many cases they were more like spectator sports.

Moving to a more demanding model will require a substantial investment (15-30 hours annually) in professional development that engages teachers in the same kinds of demanding research experiences we hope to see them demand of their students.

Just as no one develops stamina by watching others run up and down a basketball court, students will not learn to think for themselves by cutting and pasting the thinking of others.

"Thought by association" is an unproven notion.

Credits: The photographs were shot by Jamie McKenzie.

Some of the icons are courtesy of Jay Boersma's site

(http://www.ECNet.Net/users/gas52r0/Jay/home.html).

Copyright Policy: Materials published in From Now On may be duplicated in hard copy format if unchanged in format and content for educational, nonprofit school district and university use only and may also be sent from person to person by e-mail. This copyright statement must be included. All other uses, transmissions and duplications are prohibited unless permission is granted expressly. Showing these pages remotely through frames is not permitted.

FNO is applying for formal copyright registration for articles.

From Now On

From Now On