Visit the FNO Press Online Store at

|

|

| Vol 12|No4|December|2002 | |

|

Please feel free to e-mail this article to a friend, a principal, a parent, a colleague, a teacher librarian, a college professor, a poet, a magician, a vendor, an artist, a juggler, a student, a news reporter or anyone you think might enjoy it. Other transmissions and duplications not permitted.

(See copyright statement below).

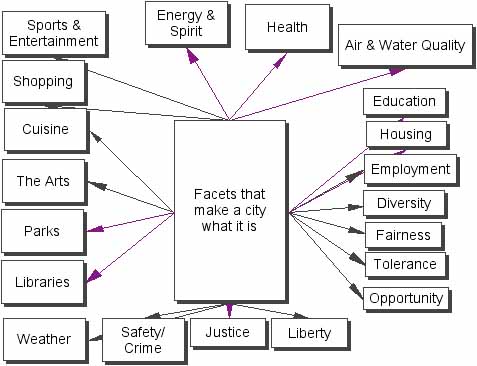

This is a preview chapter from Jamie McKenzie's newest book, Just in Time Technology: Doing Better with Fewer now shipping. Chapter 18 - Other Worldly LearningHow can we best equip students to build their own meanings? To find their own truths? To pass beyond secondhand truths or cut-and-paste thinking? We can combat the virtual social studies described in the previous chapter by equipping students with critical thinking skills that will empower them to ferret out the darker truths and strip off the pancake makeup that often conceals the reality of life in any city. While the examples and the focus in this chapter may be upon social studies, the challenge of finding truth obviously crosses over into the other disciplines as well. Mapping Out a Real City If students begin their study by creating a complete mind map identifying all of the facets of a city, they are more apt to emerge from their investigations with a full picture. They are less apt to take at face value the portrait offered by the city and its promoters. It might help if they learn about one city as a whole class first so they can appreciate how all of the facets combine to shape the identity of the city. Once they have studied New York or Sydney with the guidance of a skillful teacher, they may be able to apply a similar set of facets to Hong Kong or Portland. If students start by gathering everything they find about a city, they might build a huge pile yet be completely unaware that big chunks and entire categories of information are missing. They only know that they have big piles and tend to equate the size of piles with the growth of understanding. These piles may tell them little about the true character of the city, but longstanding school rituals have placed little emphasis upon the gathering of small amounts of pertinent information.

What’s Missing? If students do a good job of creating subsidiary questions to match each of the categories in the diagram above, the nature of research is changed radically. Under “Weather,” the student might ask a dozen questions such as:

Under “Housing,” the student might ask a dozen questions such as:

With such a full listing of important questions, the search for understanding will focus upon filling in the blanks.

The Advantage of Juxtaposition This kind of study works best when students compare and contrast several cities on the facets in the table. Without a comparison, it might be hard for the student to appreciate the import of the data being collected.

Juxtaposition helps to provide a context within which to make judgments. Without these comparisons, the facts about crime, weather, and housing may not mean much to the students.

The Advantages of Teaming Collecting sufficient data on all the key facets listed in Figure 17.1 is an enormous challenge - one well suited to team efforts. A teacher might ask four students to carve up the list so that each one gathers information about 4-5 facets about two cities such as Sydney and Perth. As each student becomes expert in certain facets, the team begins to share findings and decide their combined import. The Veracity Model We equip students with six or more questions to help them measure the level of veracity they have attained through their research efforts.

Types of Bias

What are the main filters that might block students from a truthful view of a place? How can students learn to look beyond these filters? Compare and contrast the filters listed below. Which is most apt to distort or block the understanding of your students? 1. Propaganda Information is carefully selected to create impressions about the quality of life for citizens. This kind of biased treatment of information is also intended to sway decisions by appealing to the emotions (fears, dreams, etc.) Propaganda often uses partial truths, exaggeration, and related tactics to stir an audience. The source of propaganda is usually a political group, the government itself, or some interest group with an ax to grind. 2. Marketing Marketing may use some of the same tactics as propaganda, but it is motivated usually by market interests, trying to sell products and experiences. Propaganda is more about selling ideas and action proposals. Marketing shapes information to satisfy the dreams, wishes, and needs of the consumer. In an effort to win tourist confidence, for example, a city might play down any recent problems with street crime. 3. Class How we see or report the world may differ according to our place in that society. A judge or banker might live high on a hill and see life from up in the clouds while a street sweeper might have a different perspective, different air quality and different water quality. If the reporter is content with life and her/his position within the society, the resulting stories and information may be slanted by those attitudes and life experiences. Insulated from the suffering and difficulties of life at the bottom of the social pyramid, the reporter may describe the city through "rose-tinted glasses." Conversely, someone with much life experience at the bottom of the pyramid may devote all of their attention to the slime, pollution and social problems that bombard them day after day. Roses? It may have been a long time since they have had a chance to smell or see them. 4. Ethnocentrism There is always some danger that we will read or translate information through the blinders, lenses, and attitudes of our own culture. Our students may be locked into the values of their own town or group or nation. They may be a bit swift to judge other groups or cultures from a superior vantage point. They may not view the new and different culture as a potential source of inspiration. Related to this might be the creation of information about a foreign city or country by our own country fellows - an Australian view of San Antonio, a Canadian view of New York, an American view of Hong Kong. The source may not employ local people to create the information at all. Smart chefs allow for fusion. They allow the influence of other cultures to enrich their own. 5. Ignorance Much less intentional than the previous types of bias would be information flawed by the creator's lack of background knowledge, training, expertise, and judgment. Some people do not know what they do not know. They pose as an authority without owning any of the qualities that should accompany that status. Anyone can create a Web site and pretend to know something. Can we encourage our students to challenge the authority and value of the information resources they encounter, whether they be print, analog, digital, or spoken? Limitations of Mainstream Sources When students first turn to the Net to learn about cities and nations, what kinds of information, images, and conceptions predominate? Take a look at what types of information the following four sources have to offer about Hong Kong (or any other city) and note the limitations of this type of information. What are the strengths? the weaknesses? • Source One: Yahoo - http://search.yahoo.com/ • Source Two: KidsClick - http://sunsite.berkeley.edu/KidsClick!/ • Source Three: Google - http://www.google.com • Source Four: CIA Data - http://www.cia.gov/cia/publications/factbook/ The reader will quickly see that these sources tend to emphasize the tourist’s and westerners’ view of foreign cities such as Hong Kong. Much Web development is funded with marketing money aimed at attracting visitors. As a result, much of the information offered has been sanitized or eliminated. It may be difficult to find information about bad water, hygiene or air quality from such sources. Ethnocentrism is the tendency to view and judge other cultures through the values, perspectives and bias of one’s own culture. In the worst of cases, this approach can damage relations between the two cultures, as when a business person or diplomat fails to study the culture and traditions of a host nation with proper respect and badly mangles exchanges by showing an ignorance of proper rituals and behaviors. In other respects it means blocking one’s mind to the many deep lessons to be learned by exploring different cultures with an open and appreciative mind. Many Western business leaders, for example, have grown to embrace and employ some of the tactical approaches associated with Taoism, adapting the best of Eastern culture to enrich business life at home. In addition to the marketing focus and ethnocentrism of many conventional Web sources, some of the so-called child-safe sites such as KidsClick and Yahooligans rely on Web sites created by American school children to tell us about other countries such as Australia. While it might be fun for students to read what other students think about Australia, these sources hardly meet the test of authority and reliability. We would hardly want to build our research on foreign cities upon the writings of young people who have never actually visited those cities. Alternative Sources - Triangulation What are the best ways to equip students with the predisposition and the skills to challenge conventional wisdom and marketing claims - an informed but constructive skepticism? How can multiple sources protect against propaganda and distortion? Have we been looking for truth in all the wrong places? Where should we be looking? Where do we want our students to look? No matter what the city, the topic, or the question, there are strategies likely to help researchers find alternative sources and points of view. 1. Ask the critics. Take the time to figure out who might not agree with the party line, the conventional wisdom, and the way things are "spozed to be." Sadly, local newspapers can generally be counted upon to serve up generous helpings of slander and trouble, but their articles are often missed by search engines. Students might proceed directly to a global listing of newspapers such as http://www.totalnews.com/. While the critics may not be prominently listed on major Internet listings, they can often be found my combining a major search term such as "Hong Kong" with critical verbs or nouns such as "dispute, controversy, failings, problems, issues, etc." We can teach students to look for Web sites, listservs, publications, and other sources where critics may vent their feelings. 2. Ask the helpers. When it comes to the darker side of life, helping agencies are often inclined to paint life in vivid terms, in part because this strategy often leads to bigger donations and more commitment to the cause at hand. Just how bad is the homeless problem? Ask the Salvation Army. 3. Contact real people real time. E-mail makes it possible to ask questions directly to private citizens, experts, government officials, school children, and senior citizens. |

|

Back to December Cover

Credits: The photographs were shot by Jamie McKenzie.

Copyright Policy: Materials published in From Now On may be duplicated in hard copy format if unchanged in format and content for educational, nonprofit school district and university use only and may also be sent from person to person by e-mail. This copyright statement must be included. All other uses, transmissions and duplications are prohibited unless permission is granted expressly. Showing these pages remotely through frames is not permitted.

FNO is applying for formal copyright registration for articles. Unauthorized abridgements are illegal.

|

From Now On

From Now On